The title of this exhibition refers to a short story by Nabokov. A minor official takes a train on a “pleasure trip,” is struck by the landscape, and wishes to remain there. But no such luck: the group clenches its steel jaws, and a simple everyday plot turns into horror. The story was written in 1937, when the constructivist utopia of the early XX century was collapsing with a crash — and Boris Kocheishvili was born three years later, in 1940. As the artist was discovering the world, the cloud, the lake, and the tower had already lost their static magnetism. The turn of the 1940s–50s was a time of change. All parts of the world fell apart, set into motion, rose into the air, and forgot their original form.

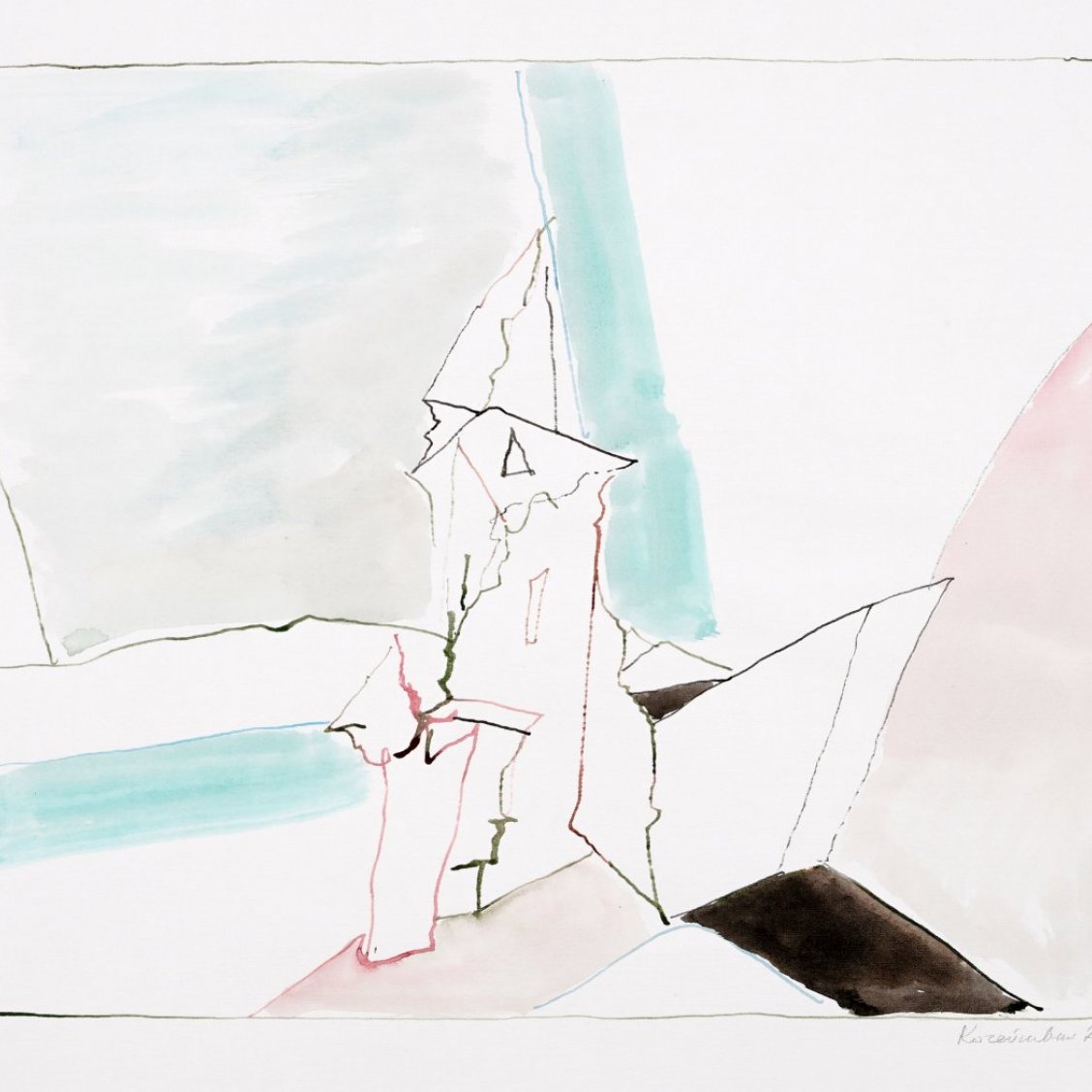

The center of Kocheishvili’s universe is a swift river with shifting banks, and his art is a walk through its surroundings, where nothing is permanent. In this he differs from the conceptualists, who build their art like a system of footnotes — a witty commentary on the social contract. Kocheishvili offers no commentary, nor does he assign society any special weight: the artist is not an observer of the landscape but part of it. His world has no need for ironic footnotes. It is a painterly ruin, within which doors and windows open by themselves, the sky clears only to then pour down a torrential rain of strokes, and all the elements become slanted, like the rain: sometimes it is an eighteenth-century fantasy ruin, sometimes an unfinished shack, or simply sheets of iron and planks thrown down by the shore, in the grass and sand. The people in these paintings are only guests; they determine nothing here, ultimately disappearing among other concepts — trees in a philosophical forest, where the author wanders aimlessly.

Yes, Kocheishvili is a poet of inexactness. He values emptiness and, so to speak, leaves reality alone. A gesture that today is almost impossible, since digital information fills every second of our time, pushing us toward completeness, toward neatly packaged predictability. A poet, but also, in another sense, an architect. While a person of the 2020s still vaguely hopes to live with a view of a lake and a tower, Kocheishvili long ago built his own tower from whatever lay at his feet and became the sole master of boundless mental landscapes — asking no one’s permission and waiting for no better conditions; simply stepping aside from any kind of artistic agenda. This is where the path to true art lies: first emptiness, then the decision not to retreat. The materials are not luxurious, yet so convincing that no others can be imagined: hardboard panels, cement, drawing paper, markers, ink, acrylic. What does Kocheishvili build? Light scaffolding, on which a spectacle of plastic phenomena unfolds. The scriptwriter is nature, weather, time — and not a single scene is ever the same.

— Nadezhda Plungyan