If we picture a selection of classic 19th-century Russian paintings, we immediately find ourselves in the forest: "Morning in a Pine Forest", with its iconic bears, the works by Levitan, Vasnetsov, and Klever… In the 20th century, Futurism and the era of total industrialization raised the city, the machine, and speed as their new banners. Nature became morally outdated, left to be painted only by aesthetes and escapists. (And yet, even in the 20th century, no one dared to dismiss the almost magical Russian word dacha.)

Today, this theme has regained its urgency. Citizens of the post-industrial world, overwhelmed by an excess of information, flee to the forests in search of renewal and reset. It seems that every now and then, word spreads of yet another acquaintance who has joined the ranks of so-called downshifters—abandoning a prestigious job and giving up on a career in favor of freedom, creativity, and life in nature.

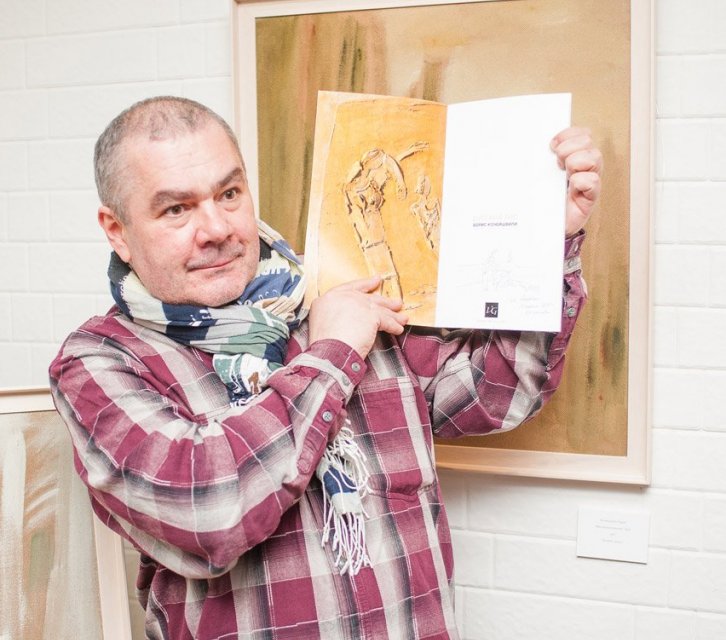

In this light, the women wandering freely in the open air in Boris Kocheishvili’s picturesque series, presented at the exhibition, could be seen not only as Venuses emerging from the forest but also as weary city dwellers retreating into it. It is no coincidence that these nude dryads bear simple Russian names: Maria, Katerina, Elena.

Art historians and curators often repeat that contemporary art is primarily about a relevant statement, an original reaction to the processes shaping the world today. It is a fair demand: mere reproduction is outdated, and the omnipresence of images is already overwhelming. But in truth, every artist who has entered the grand history of art has done so precisely by offering a fresh and timely perspective on modernity and its defining forces.

Boris Kocheishvili undoubtedly belongs to that lineage of masters with a singular artistic vision and language. Though he does not provide conceptual commentary on his works, it is clear that his art is built on a plasticity and thematic depth uniquely his own. His work presents two of the most pressing narratives of contemporary existence. First, the paradox of solitude—unexpected, even in a world overflowing with communication—along with the complexities of human relationships. And second, the way the human figure navigates the rhythms of a world caught between the old and the new century, balancing on the threshold of time.